Wudangshan 108 is both complex and beautiful, and these are the qualities that drew me to it the first time I saw it performed. I knew only that I wanted to learn and be able to do the form well, and I was fortunate that my late husband encouraged me to pursue it. Soon, in addition to attending classes and practicing, however, I was also reading books in an effort to understand Daoism and the principles underlying taiji movement. This full-immersion style had also characterized my ten-year engagement in poetry, and I confess there was a time when, though I was still writing, I had considered redirecting all of my energies to taiji. As fate would have it, however, within a two-week period in 1997, my chapbook manuscript won the Harperprints Poetry Chapbook Competition, and the editors at BOA Editions selected for publication the book-length manuscript I had been working on for seven years after receiving my MFA degree. I felt, in part, that I was being called back to poetry.

In 1999, I traveled to Missoula, Montana, to interview the late Patricia Goedicke, one of my poetry teachers. While I was her student and even much later, she repeatedly encouraged me to open up to the larger, Whitmanesque sweeps of language in my poetry. On that visit, however, when I came inside after practicing taiji in her back yard, she said, “Now I understand.” Unbeknownst to me, she had watched me practice, and she said that it looked as if I were making boundaries visible as I moved through the postures. I love this image because it reflects the way I think about writing poetry, too. While several of the taiji teachers I’ve worked with resist the idea of postures and substitute the word “movements” to emphasize the flow from one posture into another, I think of the brief pauses marking the postures as being like the place one has learned a line should break, and it takes practice to tune the inner ear to know such points of balance; as with poetry, that place determines the meeting ground of strength and weakness, of risk and expressiveness.

Many of the corrections a taiji teacher makes are attempts to impart a vision of the form as a whole and an occasion for students to learn without judgment what their limitations are—both of body and of mind—at that particular moment in their development. In taiji, one’s medium is the body, and form marks out a place for exploration and discovery. So for me taiji is not only an art of transcendence but also of immanence, which is precisely why I love it so much. Here one comes face to face with the miracle of the incarnation. How is it we come to inhabit these bodies? Over the course of my engagement with taiji, I have known myself as being in but not entirely of the body only a few times, and such experiences leave traces even in an often skeptical consciousness like mine.

Needless to say, I do not wish to be “out of nature” as Yeats used the phrase in “Sailing to Byzantium”; rather, I wish to know the “dying animal” I am “fastened to” in order to go deeper into it—because it, too, is part of nature. Poetry and taiji help me to do this—poetry through motion in apparent stillness and taiji through stillness in apparent motion. In poetry, the body expresses itself through the mind, and in taiji the mind expresses itself through the body. Body and mind—these are my two fishes, another name for the yin-yang symbol, and it’s interesting to consider that a fish must move to breathe and so to live. With sight, where the two fields of vision overlap, we perceive depth; whatever it is I know as spirit is like that.

For a long time I thought I was drawn to taiji rather than zazen or yoga because I had been an athlete in my youth, that my body still craved motion, which is a partial truth. I have found that on the physical level, practicing a long form that has been engrammed can be almost as pleasurable as a five-mile run. At higher levels of practice, however, taiji, sometimes called “shadow boxing,” also requires using the imagination to bring to life a carefully choreographed set of movements known “by heart.” It’s said that a good practitioner will so shape the patterns of movement that an imagined other becomes visible to those who have studied taiji, and those who have not can sometimes recognize when a practitioner has put his or her whole self—body, mind, and spirit—into the effort by the seemingly effortless quality of movement.

Nearly fifteen years after starting to learn Wudangshan 108, I have come to believe that the solitary aspects of the practice of taiji and of poetry are different but complementary modes of meditation, one wordless and the other full of words, that regulate threads of connection, including the inhalations and exhalations of breath. In taiji we speak of silk-reeling energy, and in poetry the unit of attention or energy is the line, a word that can be traced etymologically to flax and, when it enters Old English, means “string, row, [or] series.”

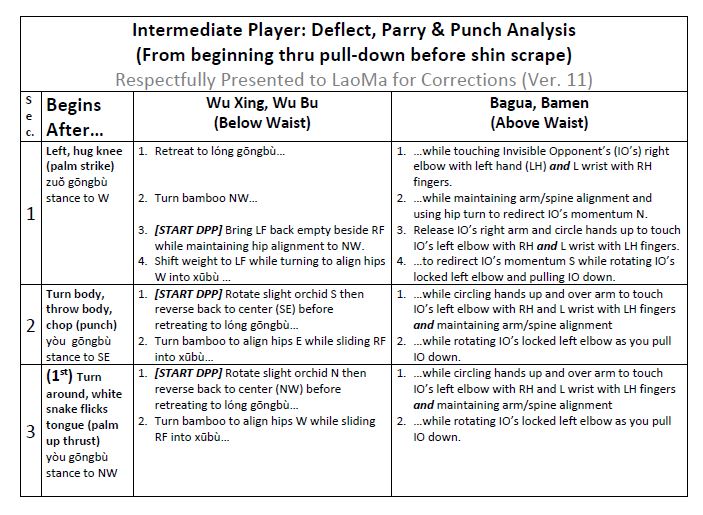

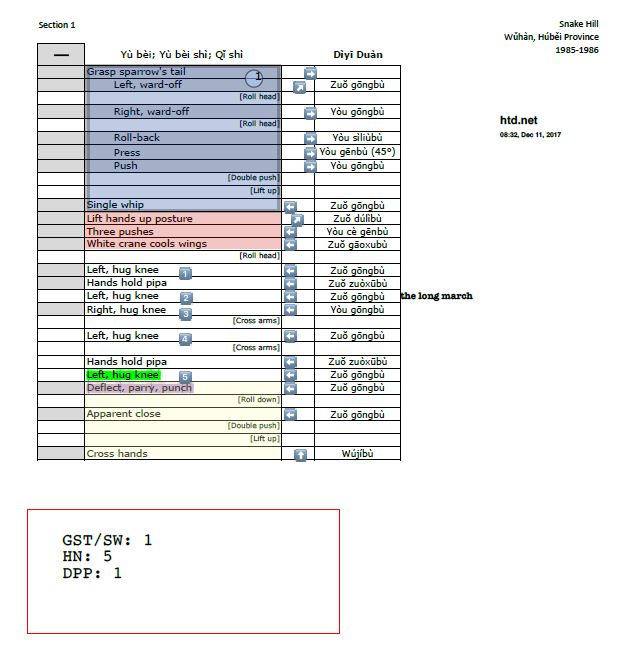

In private lessons during my period of intense training in North Carolina, my teacher would often focus on one section of the form and then offer what sometimes seemed like a non-stop series of corrections, which I never found discouraging. Sometimes it was challenging, of course; however, because it was not simply a matter of changing the position of my hand, say, but of understanding it as a problem that might originate in my feet, I had to find my own way there. LaoMa told me on several occasions during these lessons that he wanted me to learn the form as taught to him by his teacher. By this means of transmission, taiji became for me more than exercise or just beautiful movement because, however imperfectly I might be performing it, I was learning to embody a form and becoming part of a human chain that went back to Zhang Sanfeng, who is generally credited with creating this art and to whom my teacher’s teacher traced Wudangshan 108. So I have come to see this form as a “songline.”

When I practice Wudangshan 108, then, even if just a small part of it, how can I feel alone? I am no longer strictly in the present but have, instead, brought something from the past into it. And yet, as if it were an inevitable outgrowth of Daoist thought, my teacher also told me that after I mastered the form—he is such an optimist!—I would almost be obliged to put my signature on it, which I think is not about originality but about engaging with the form in the light of the present, of which I am a part; in other words, I am to be not just a place holder but a meeting ground where what is essential in the form is carried into the future so that the line may remain unbroken. This requires learning from the wisdom of the body what is substantial and insubstantial at any given moment and how, because movement is change, one becomes the other for as long as this beautiful wave of postures lasts.

Surely the journey to mastery of such forms lasts as long as life does and may suffer many interruptions, as mine certainly has. It is so strange to be writing in anticipation of a visit to work with LaoMa later this summer. Though I have mostly kept a hand in taiji, in terms of time, I feel a little like a prodigal returning after a long absence. I know that in one respect, these are the sort of journeys that end only with death; in conventional terms, Dīng Hóngkuí, my teacher’s teacher, Patricia Goedicke, one of my poetry teachers, and Bradley P. Dean, my husband, are insubstantial now. And yet, for a moment, here they are, present.

When I do the whole of Wudangshan 108, I want to make my way and make visible my passage through a meeting ground that is also always precisely here. Writing poetry, I try to remember that the Chinese word for poetry is a composite of one character meaning both “word” and “speech,” and another meaning “temple”; I want to call into being that temple, whose true medium, beneath the words, is breath. Obviously, I don’t live on this plane; mostly, I just keep breathing. Because of those who came before me and left their marks, however, I can imagine it and try to keep moving, as best I can, with the hope that at some point, I will find myself standing on the threshold.

July 2012